Germany’s 2010ers are extreme.

At the Rudi Wiest tasting in New York I was poured an Auslese from the Pfalz harvested at a simply ludicrous ripeness level. The wine felt like molasses on speed frazzled by battery acid. I stepped back and stumbled to catch my balance. I felt like someone had just thrown a bowling ball at my face that was laced with dark sweaty fruit and unripe limes.

This is a tricky vintage friend: beware of any merchant trying to sell you some easy story.

There just is no simple narrative here. In some cases the 2010 Germans are extremely bad, in some cases they are extremely good.

Terry Theise, ever the word-smith, summarized: “The headline is, what’s good is absurdly good... What’s not good is a mess.”

|

The keywords for 2009 are ripeness, power, botrytis and acidity.

In the great examples, these elements come together with Wagnerian proportions to create wines that are plush, dense, maniacal, deep and very, very layered and even more complicated. If the stuffing here would be too much for any normal wine to handle, in 2010 this is not a problem as the acidities are amongst the fiercest that German winemakers have seen in a generation or two. When the disparate elements here are married, the results are simply riveting and 100% unprecedented.

When they are not in alignment, you get the bowling-ball effect. So be careful.

I want to sell German wine. I want to sell a lot because I love the wines, the people making the wines and the places the wines come from. This is more than just business. I love the startling freshness of Riesling and its supreme, riveting clarity, its specificity. I love Graacher Domprobst and Ayler Kupp and Bockenauer Felseneck and Westhofener Morstein. I love that they are all still so freakin’ inexpensive, short harvest and strong euro be damned.

Yet this vintage, I think, is best chopped up in the following manner, for the following people.

1) For the casual, everyday buyer…

...as well as the fanatic who just wants some super-fun early drinking, there are some wines in 2010 that are going to FREAK you out in the greatest possible way. For REEEEEEEEEDICULOUS drinking over the short term (say the next 6-24 months) I can’t imagine you will find more shockingly intense wines out there. Rieslings gone insane, maniacally exotic fruit paired with shivering acids and enough electricity to power every major city on earth for the next gazillion years, give or take a few. These wines are beyond Technicolor – they are kaleidoscopic, spasmodic, super-freaky, ultra-violet wines of a most preposterous nature.

Writes Terry Theise: “2010 is the most concentrated vintage I’ve ever tasted in Germany. Forget ‘vinosity;’ these babies are as dense as paperweights.”

And these wines can be dirt cheap; they should be drunk with wild abandon. Don’t cellar them, don’t covet them, don’t put them in your wine fridge – DRINK THEM. Seriously.

|

2) For the German wine geek…

For those of you serious about supporting and cellaring German wines there are without a doubt some profound examples to be had in 2010. This is a vintage of extremes and some of these wines (based on their analytics alone) must have a potential for good perhaps never before known to the mighty Riesling grape. Yin for yang, some are also train wrecks.

This vintage will not be an easy journey. (Please take this as a rallying cry and not a deterrent.)

To begin with the euro has been stronger this year in comparison to last year, making the wines more expensive to begin with. Moreover, quantities are seriously down (anywhere from 20% to a jaw-dropping 60%, depending on who you talk to) so the wines are going to be harder to find and in shorter supply. Finally, it’s a vintage that favors the noble sweet wines, the Baroque masterpieces that really do deserve a few decades before they are disturbed. From what I've heard, J.J. Prüm will not bottle any Kabinetts in 2010; those that labeled bottles as such are most likely dealing with Auslese-level ripeness levels. (Not that such-labeled Kabinetts can't be compelling in 2010; witness A.J. Adam's psycho-Kabinett - wow!)

But as for the great dessert wines of Germany, they just need patience and it saddens me, but patience is not a virtue our culture currently celebrates. This remarkable genre of wine suffers a bit more every year.

For you brave souls who go forth, despite the challenges, there will be some serious rewards to be had. But there’s a lot of crap too, so just find someone you trust, and talk to them.

It will be worth it.

As for myself, I’m sad to report that this was the first year in quite a few years that I did NOT make it to Germany, despite the fact that 2010 is one of the most important vintages of my life.

|

These two random facts are not unrelated: My first child was born in August of 2010, making an early-year trip just a bit too much for me, my wife and maybe even our new son, Henri Wolfgang (French and German grandparents – c’mon, you’ve always wanted to know a Wolfgang). Yet, obviously, being obsessive-compulsive, I’m already worried about Henri’s cellar and so I’ve been working on this report for a very long time, emailing just about everyone I know in Germany, not exactly weekly, but at least monthly, for updates on the 2010ers.

How are they doing? Who’s great? Who’s good?

I’ve found myself awake at 2am more than once emailing various winemakers, begging for random magnums and double-magnums to pour at Henri’s wedding. Never too early to start worrying about the wine at your son’s wedding. (Don't believe me? Well, let's just say there are three of these in the cellar for Henri's wedding day or some other day of similar emotional weight say 20 to 40 years in the future.)

So I’ve heard a LOT about the vintage. I’ve read everything that’s been written or at least most of it. Klaus-Peter Keller has been patient with me as have Andreas Adam and Florian Lauer. Florian, by the way, also had his first child, a girl, Louise, in late summer, just days after Henri was born. (I'm not sure Florian, or Henri for that matter, knows it yet, but my plan is to have the two of them fall in love so I can retire on the Saar. Not that it's all about me.) In any event, I sincerely thank everyone for their patience and time. I’ve emailed with David Schildknecht quite a bit, who is always so busy and apologizes for not having time to answer your question in full, and then writes you a 5,000-word treatise that is at once elegant, insightful, funny, charming and perfectly punctuated. The solitary scholar in Trier, Lars Carlberg, who founded Mosel Wine Merchant, has now left to begin a new small portfolio under his own name and has responded to every email with patience, kindness, specificity, and his own unique perspective. He has been a massive help editing, bringing the same attention to detail to this manuscript that he brings to the wines he selects. John Gilman of View from the Cellar and Dan Melia of Mosel Wine Merchant and a number of other random German wine dorks have showered me with their insights.

Whatever intelligence this report has, it’s because of them. Whatever shortcomings, those are mine.

And yes, I’ve also tasted a bit.

Rudi Wiest usually stuffs a bunch of tank and barrel samples into his luggage and brings them in for a few die-hard geeks to taste. Then I’ve gone to the major 2010 portfolio tastings which have unfortunately been short of 2010ers. There just aren’t many to go around.

It’s a short vintage – the best of them are going to disappear quickly, so, like myself, you might have to ask for one shot and you might not get more than that. Terry Theise, who really is never that pushy a sales guy, concludes his vintage summary verily: “Please understand this isn’t a vintage you can afford to ‘buy later.’ The smart money says to grab now and don’t look back.”

Weather Report: Extreme

2010 in Germany is an unprecedented vintage.

Theise quotes Carl Loewen saying the following in regards to 2010: “I never experienced a year like this one. Must weights like the best years and acidity like the worst years.” Over a long dinner at Franny’s in Brooklyn, consisting of perhaps an unhealthy amount of carbohydrates, Dan Melia of Mosel Wine Merchant quoted Florian Lauer as saying that the vintage had “the ripeness of 2020 with the acidities of the 1960s,” which is to say over-the-top ripeness and acidity levels like “the good old days.”

The reason?

No one really knows, though there are some obvious factors to hang your hat on.

First of all, there was an uneven flowering – an event that is not all that unusual and really just means reduced quantities of grapes, it doesn’t do much to quality. (If anything, the reduced quantities probably saved the vintage, the massive extracts in the few remaining berries buffering their wicked natural acidities.) The summer was warm, July was hot. So hot that the vines went dormant, just shut down to save themselves. This meant that nothing progressed; sugars didn’t really go up, acidity didn’t really go down. This summer dormancy is one reason in 2010, perhaps even more than most vintages, harvesting late was critical. In one exchange Schildknecht, ever the moderate, wrote to me that harvesting late in 2010 was, “surely beneficial if not critical.” August was fine – not exceptional really but more importantly, it was not sunny. This meant that the acidities, which had already been held in check in July, didn’t do a whole hell of a lot in August.

This is strange folks.

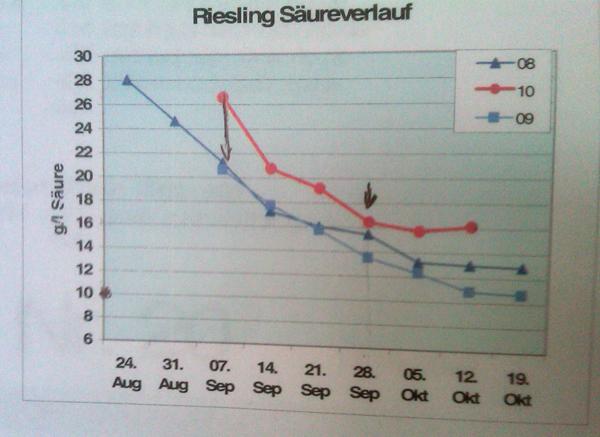

Graphs are for scientists and political advisors, I know, but take a look at figure 1, below – it charts the progression of acidity through the fall. The first thing you should note is that at the beginning, roughly September 1, the grapes of the 2010 vintage had acidity levels well, well above anything from 2009 or 2008 and 2008, as many of you know, was not a shy vintage. Those wines had some bite.

You’ll also note that as of about October 5, the acidity levels hold steady and even start to rise again. This is bizarre (as ripeness progresses, acidity usually drops) and the culprit? Botrytis, aka noble rot – it concentrates sugars and sweetness, but as the water is removed from the grapes it also concentrates acidity: Thus the crazy jolt of many of the 2010ers, especially the big boys (Auslesen, BA, TBA).

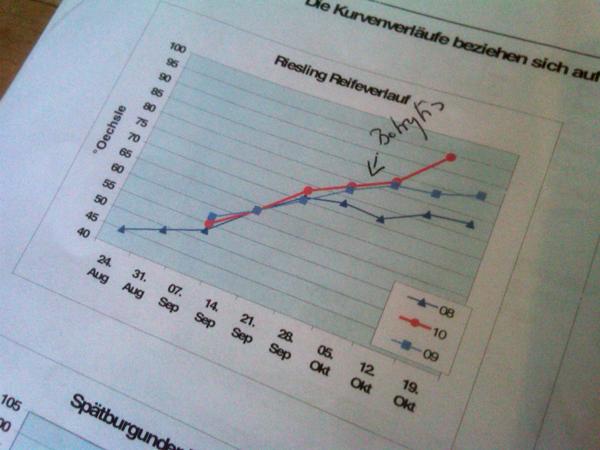

Stick with me here, just one more graph. This is the ripening of the grapes – their sugar development. You’ll note things are basically identical to both 2008 and 2009 until mid-September, that’s when 2010 and 2009 pull away from the more-cut 2008 vintage. No surprises there. Then, however, at about the beginning of October, the sugar levels of the 2010ers start to dramatically pull away from even 2009. Why? Again, Botrytis. The grapes start shriveling and condensing the sugars and there you go.

A freak is born.

Specificity (Details Matter)

There is no easy formula for buying in 2010. It’s not that the Mosel was good and the Rheinhessen was bad, or that Wehlen was good while Graach was bad, or that Graacher Himmelreich was good while Graacher Domprobst was bad.

Some people said things got better as you headed north, that the Pfalz was kind of a disaster. But Theise didn’t seem to agree. By most accounts the Nahe seems to have gotten through the vintage with the least amount of massive shake-ups.

In any event, very smart, knowledgeable folks have differing opinions about the vintage. The only constant in 2010 is the lack of consistency - in wines, in opinions, etc.

|

The 2010 vintage is about each individual wine.

This vintage may have produced some great, great wines – extreme Rieslings that will go where no Riesling has ever gone before. Seriously, there are experiences to be had in this vintage that have never existed in the vinous world before and I think you’d be remiss to miss it. There are bionic Rieslings in 2010 that will glow in your cellar for 50+ years, wines that simply throb with potential. Henri’s cellar is full of promise.

That said, this is just not a great vintage. It was too hard, too fraught with dilemma. This is a vintage to love your grower because they worked for these wines.

One grower, commenting on the vintage, eloquently wrote: “God damn that was hard.”

The vintage, in most instances, is geared towards feinherb (off-dry) wines and those with more noticeable residual sugar, the so-called "fruity" wines as the Germans like to call them. I’m talking about Kabinett, Spätlese, Auslese and beyond. To get even more specific, from what I hear the strongest wines, the wines that make the most sense in the context of the vintage, are the grandiose Auslese and BA and TBA and Eiswein. From what I hear there are some once-in-a-lifetime noble Rieslings to be had this vintage. It's sad, but these genres of German wine get more and more unfashionable with every passing vintage, so as short as the vintage is, my guess is the winemakers will be holding back some quantities here for later offerings.

Although there are some very good as well as great dry Rieslings out there (Tim Fröhlich, by many, many accounts, made the greatest dry wines of his career in 2010), in general this is a vintage where a bit of residual sugar went a long way in taming the icy acidities that prevail. So be savvy in this vintage buying dry wines; talk to your wine merchant and hopefully you trust your wine merchant. (If you don’t, consider buying your German wines here.)

“De-acidification”

This is the topic that’s on everyone’s lips in 2010 and maybe it’s terribly important, maybe it isn’t. Honestly, it’s hard to say and I, along with many in my rough generational slot, simply haven’t had extended experiences with wines that have been de-acidified. In this regard it's somewhat entertaining (and sad at the same time) to hear the chatter on all sorts of wine blogs and internet forums decrying the vintage as something to skip almost a priori because of the de-acidification that may or may not have taken place. Not even a year old and already there are so many who seem to have no doubt what this vintage will become, from the Mosel to the Rheingau and from dry wines to noble sweet wines. I don't exactly understand how an audience that should be celebrating the diversity and specificity of German wines seems to have little qualm with writing off a country's worth of wine with a post or two. But so it goes.

|

For those who want to try and approach the vintage with a bit more calm and humility, here’s the short story as per de-acidification: Acidities were so high in 2010 (the reasons we can analyze were presented above) that many winemakers found themselves in an unprecedented position: they had wines (or musts) with too much acidity. I've heard stories of very experienced winemakers (we're talking with decades of winemaking under their belt) having to grab dusty how-to books off equally dusty bookshelves. Many, many winemakers had just never had to worry about de-acidifying their wines. It's impossible to over-emphasize this point.

So, how do you go about de-acidifying?

Let's start with the least invasive methods; obviously there are ways to minimize acidity at nearly every step of the winemaking process. You could harvest later, for example. That tends to allow acidities within the grapes to naturally drop while sugars rise. This is why, as I pointed out above, late harvesting in 2010 was critical. Those who played it safe, who harvested early, paid a price in this vintage.

In the cellar, winemakers can try and "balance" the wines by simply leaving more sugar, though as Schildknecht pointed out to me, “that’s unacceptable to most German vintners and consumers who ‘must’ have their Rieslings legally trocken.” This is why, however, the smart money generally speaking seems to be on the fruity wines in 2010.

There are a few other ways to mitigate acidity. One is simply illegal, and that’s just adding water. Another method is largely considered anathema to what Riesling should be to many: malolactic fermentation. Malolactic fermentation is what makes that California Chardonnay taste so buttery; it’s a conversion of malic acid (think green apple) to lactic acid (think buttermilk). In the simplest of explanations, this process takes a very sharp acidity and buffers it - thus you can imagine the temptation in this vintage. I have heard that numerous winemakers on the Saar and Ruwer experimented with some malolactic fermentations, but it's hard to confirm any concrete details. And as with most things, the story with malo is not as simple as we'd like it to be. It can be naturally occurring (especially among certain producers) or helped along or artificially brought on. The malolactic fermentation can be full or partial, and it can influence all sorts of wines in many different ways. I write this neither to try and justify nor condemn the results or the practice - just to acknowledge its complexity.

Finally, you can age the wines, both in cask and in bottle – time, after all, tempers all things. Florian Lauer mentioned at some point (or maybe it was Dan Melia who mentioned to me that Florian [or some other grower?] had mentioned it to him???) that in years gone by, most growers would have simply held the wines. Patience. In other words, the wines would have been buried in the cellar to develop and integrate at their own pace. But extended aging is not really financially feasible anymore and I for one don’t feel like I’m in the position to tell a grower to take out some loans and keep a year's worth of work in the cellar for 10 years so that when it's finally made available, we have a better idea of what we're really getting.

I sort of think that should be our job as consumers. Give the wines the time they need and instead of curating the 100-point cellar or looking for your own idea of perfection, let the wines be what they will. Find growers you really like and support them year in and year out because you appreciate the work they are doing, because these wines represent a tiny bit of culture that is worth supporting. I'm old fashioned like that.

Now, instead of the aforementioned methods or (more likely) in addition to them, there are other ways to literally take out the acidity present in the must or the wine itself. This is really what people are referring to when they mention the d-word. This is all, of course, technical and involves all sorts of knowledge and expertise that I just do not have, so I'll just outline the basics, as I understand them.

Skipping altogether the process one uses to de-acidify (be it tartrate precipitation or "double-salt" de-acidification), the first decision a winemaker who wanted to de-acidify in 2010 likely faced was whether to 1) de-acidify the must or 2) de-acidify the wine itself. Most people I've emailed/spoken/texted/Facebooked with believe that de-acidifying the must is the preferable way to go. The downside here is that one has less control over the final wine, as fermentation and maturation alter the profile and expression of acidity. In effect, you're tweaking something before it gets tweaked again - trying your hand at watercolor before running your finished work through the dishwasher. The upside, so they say, is that this method results in wines that are more seamless, that show a better integration of acidity and fruit, etc. De-acidifying the finished wine is a more exact process (again, as the wine has already gone through fermentation and maturation), so you have more control there. But many say this process is more damaging to the wine.

|

And this leads us to the more (most) important question: Does any of this really matter? If you like how a wine tasted, should you care how it was built, so to speak?

I think the answer here is, unfortunately, both no and yes.

No, because, for the great majority of wine drinkers, a bottle of wine is a means to an end, not an end in itself. It's there to be enjoyed and if you enjoy it, well, does the fact a grower used partial malolactic fermentation and a double-salt de-acidification matter??? The correct answer here is, no, it does not.

At the same time, with de-acidification there are enough experienced tasters who claim it does affect the wine in both the short and long term. So, for those looking a bit deeper into their glasses of wine, I think a degree of caution is advisable in 2010.

The major concern is that the process, when done poorly (or done at all depending on who you talk to) can strip the wines of character or even damage their inherent balance or structure. Some believe that de-acidification weakens the ability of the wines to age. Schildknecht, who is one of the most anti-ideological thinkers I have ever met, wrote me the following:

"My general impression has been that the effects of de-acidification whether in must or wine are detectable and that even in very high-acid years wines whose acidity has not been adjusted are ceteris paribus more expressive, not to mention almost by definition more representative of their vintage. Furthermore, my impression has been that acid-adjusted wines do not age as well as those that weren't. For somebody who hesitates to subscribe to blanket statements or sharp dichotomies, this is about as close as you are likely to come to finding me subscribing to one!"

For the great majority of the buying public, I'm not exactly sure if alarms should go off. At the same time, for those serious about cellaring German wines, it's a good idea to educate yourself in 2010 and to make your own informed decision.

I should say that we as a store are not going to make a huge deal about which wines were or were not de-acidified, for the following simple reason: it's impossible to really know. Obviously, given the biases that many consumers may have (perhaps for good reasons), winemakers are not particularly inclined to reveal their secrets. I can't exactly blame them.

I'm confident that many growers did not de-acidify, despite what some are suggesting. There are going to be 1,000 exceptions here, but it's safe to assume that more of the dry wines will have been de-acidified than the sweet or "fruity" wines - the reasons here should be obvious. It's important to differentiate, however, between the legally dry wines (must be under 9 grams of residual sugar per liter) and those that are dry-tasting. There are many winemakers who chose in 2010 to let their wines ferment to their natural balance and these will have residual sugars in the 15 to 35+ range, yet, given the hyper-acidities, are likely to taste quite dry. Florian Lauer of Weingut Peter Lauer is a perfect example of this style; Andreas Adam of Weingut A.J. Adam is too. He's bottling his Goldtröpchen as feinherb in 2010 - you no doubt recall that the 2009 was a dry wine. While there are no doubt some Auslesen and above that have been tinkered with, even from the top estates, common sense should dictate that such examples will be fewer and far between.

At the end of the day, the real story of 2010 in Germany is going to need time - damn our need for instant truths and easy-to-digest headlines. More than most vintages, for the serious buyer, 2010 is going to ask for faith, curiosity and patience.

My own personal buying strategy

I hope this doesn't come off as pompous or presumptuous. I’m including this (short) section simply because I've been asked by a number of people what my buying strategy will be. I suppose the assumption is that this is a difficult vintage and this poor sucker (i.e., me) has to buy the wines because of his kid, so he's probably done his homework.

Well, I've tried.

So here's what I'm going to do: I'm going to buy the wines I’ve consistently loved from the growers I’ve found consistently great and put them in the cellar. These happen to be, go figure, the wines I’ve bought for the store – A.J. Adam, Dönnhoff, Lauer, Keller, Schloss Lieser, Willi Schaefer, Schäfer-Fröhlich and Günther Steinmetz among others. Because I'm buying for the future, for Henri, and because I think the heart of the vintage really is Auslese and above, that's what I'm going to focus on. I also think the Kabinetts of 2007, 2008 and 2009 are so riveting that I don't see that point in stocking up on the 2010ers (with some exceptions, including A.J. Adam's wunder-freak-Kabinett). I absolutely love the wines of Florian Lauer and I trust that his wines will make sense in the context of the vintage. I have heard Stefan Steinmetz's wines are incredibly good in 2010. I am buying Tim Fröhlich's great dry wines. And I'll be buying a good amount of the simple Kabinetts and feinherbs; after all, I need something to drink while I wait for Henri to let me open one of the three magnums of Adam BA in his cellar!

In this vintage, the curious and thoughtful palate will find much to enjoy. Let's just try and taste the vintage with open minds and focused palates, and lets bury the grand dessert wines along with the easy assumption that this vintage isn’t worth collecting.

And then let's see what happens with a decade or two. That is, after all, the fun of it.