How happy were we to see a bottle of Hansjorg Rebholz's mind-blowing Riesling in a photo in Wednesday's New York Times! - not to mention the short but savvy article wine writer Eric Asimov penned about the great quality (and drinkability) of dry German Rieslings!

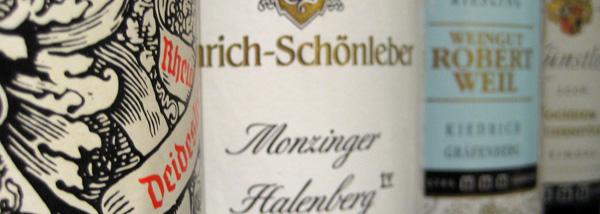

Von Buhl, Emrich-Schonleber, Weil and Kunstler stand proud and dry.

We've been passionately championing dry German Rieslings since the store opened over three years ago and it's gratifying to see the press, not to mention a growing audience of wine drinkers, get behind these great (and absurdly affordable) bottles. At this point, with a selection of nearly 30 dry German Rieslings from $16.95 and up, we must have one of the widest, deepest and surely the greatest selection of dry German Rieslings in the U.S.

Right now, we have amazing dry Rieslings from Donnhoff, Emrich-Schonleber, Furst, Karthauserhof, Knebel, Kunstler, Lang, Rebholz, Schafer-Frohlich, Spreitzer, Stein, Von Buhl, Weil, Wirsching and Wittmann! (And about 200 other German Rieslings of the sweeter variety.)

Click here to read New York Times wine writer Eric Asimov's article on dry German Rieslings.

Confused by all the terminology? Trocken, Halbtrocken, Feinherb, Charta, Grosses Gewachs, Erstes Gewachs and Erste Lage?

Then read the official Crush dry Riesling tutorial below! It's insightful and entertaining. There's even a special "Grosses Gewachs" versus "Erstes Gewachs" photo-montage below! Wow.

The Truth about Dry German Riesling

This doesn't have to be that confusing, though yes, the Germans do seem to be trying to make it as difficult as possible. Here's how it all works, in 2000 words or less. Memorize the information below and impress your friends at dinner parties! Find yourself armed with a whole new vocabulary for expert Scrabble!

Chapter 1: To be "Dry" - Trocken

The technical measure of a wine's "dryness" in German wine law is measured by the amount of residual sugar (RS) that's left in the wine after the fermentation. This is the straightforward part. For a wine to be labeled as "dry" - the German word you'll see is "Trocken"- it must have 8 grams per liter of RS or less. (Franken wines, known for being very dry, tend to have around 4 grams RS per liter.)

A wine can be called "off dry," or "half-dry" as the German word "Halbtrocken" more closely translates to, if it has between 9 and 18 grams of RS per liter. Some producers think the word "Halbtrocken" sounds too harsh and well, uh, Germanic, so they use the word "Feinherb" instead. The word "Feinherb" is essentially used interchangeably with "Halbtrocken," though I don't think it has any legal standards. A safe rule of thumb: Halbtrocken = Feinherb and vice-versa.

Simple so far, right? That's the spirit! The most important thing to keep in mind here is that sugar is, at least in this simple formula, only one-half of the equation. On the other side of sugar, we have acidity. Which is to say a wine will taste more or less dry depending not only on how much sugar it has, but on how much acidity it has. A wine with 10 grams of acidity can handle 20 grams of RS without tasting terribly sweet - take the acidity down to 2 or 3 grams and all of a sudden that 20 grams of RS tastes quite sweet indeed. As an example, imagine adding a tablespoon of sugar to some lemon juice - it's still going to taste pretty tart. Then imagine adding a tablespoon of sugar to some plain old water. Yes indeed - it's going to taste much more sweet! Thus poetic words like "balance" and "poise" somehow seem more evocative and revealing when discussing Riesling than any simple measurement of RS vs. acidity.

Chapter 2: It's a Spatlese AND it's Dry?

Here's where things get perhaps a bit confusing.

German wine, at least since 1971, has been categorized based on a system that measures the ripeness - the amount of sugar - present in the grapes at harvest. Based on this system, a grape that goes into a "Kabinett" must be harvested at a certain degree of ripeness; a grape used to make a "Spatlese" must be even more ripe - and "Auslese" even more so. This is all done by measuring the weight of the grape juice (called the "must") before it is fermented. Sugar is heavier than water, so the more sugar, the heavier the must, the higher the ripeness level. Simple.

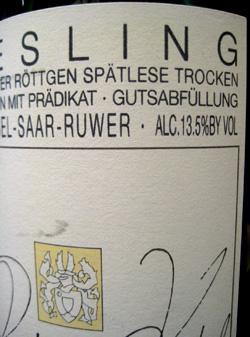

The key thing to keep in mind is that these ripeness levels refer to the grape juice BEFORE it is fermented. In other words, while the must may have enough sugar in it to qualify as a Spatlese when it's first pressed, there's no reason the process of fermentation can't gobble up all the sugar in the must so that the final wine would taste absolutely dry. What would we have then? A Spatlese Trocken! You know what they say: Spatlese Trocken happens. We in fact have a few - Stein Bremmer Calmont Spatlese Trocken and Knebel Winninger Rottgen Spatlese Trocken to name but two.

How would a Kabinett Trocken differ from a Spatlese Trocken? Both, after all, will be dry. It's a hard question to answer cleanly since so much depends on the region, winemaker, vineyard, etc - but a safe generalization is that a Spatlese Trocken will taste bigger, richer with more heft than a Kabinett Trocken, which will probably be leaner and crisper.

Now, very often (maybe even most of the time?) the ripeness levels do correspond to the amount of sugar remaining in the wine after fermentation, so a "Spatlese" does taste sweeter than a "Kabinett" and an "Auslese" sweeter than a "Spatlese." This is a pretty safe bet most of the time, but it does not have to true all of the time - especially in this brave new age of dry German Rieslings in the U.S. So beware!

Chapter 3: Charta, Erstes Gewachs, Grosses Gewachs

Now we enter Winegeek territory. You have been warned. (Though the special "Grosses Gewachs" versus "Erstes Gewachs" photo-montage is coming up too, so that'll be fun.)

This becomes a bit complicated, and a bit controversial, so I'll try and simply explain the most obvious points and largely avoid the philosophical, angst-ridden issues.

All of the above - Charta, Erstes Gewachs, Grosses Gewachs - are various ways of attempting to identify the greatest dry German Rieslings. That's about it, really. These are the "Grand Crus" of dry German Riesling. In fact, "Grosses Gewachs" translates roughly to "Great Growth," "Erstes Gewachs" to "First Growth." So that's that.

What's the biggest difference between all these various denominations? The region in Germany the wines come from. Enjoy the pictorial part of this tutorial below.

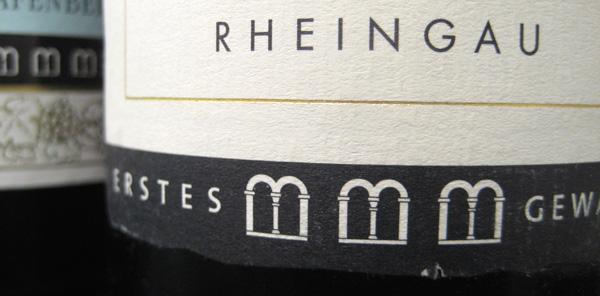

On the left, in a poetic state of non-focus, Weil's Erstes Gewachs "Grafenberg" - to the right, Kunstler's "Kirchenstuck" sports the "three arches" of the Erstes Gewachs.

Charta and Erstes Gewachs can only come from growers and vineyards in Germany's Rheingau. If a wine is Charta, it'll say "Charta" somewhere on the label; if it's an Erstes Gewachs, it'll sport the highly fashionable "arches" of the Erstes Gewachs. Usually, though not always, the arches are lined up in a set of three, along the bottom edge of the label, as in the Kunstler Kirchenstuck label above.

Just to the right of Halenberg - BOOM - there it is - the "grape-bunch stamp" of the Grosses Gewachs. Ditto with the Schafer-Frohlich, the "grape-bunch stamp" rests just to the right of the word "Riesling."

Grosses Gewachs applies to growers and vineyards basically everywhere else in Germany - in Franken, the Pfalz, Nahe, the Mittel Rhein and Rheinhessen. These bottles have the cool "grape-bunch stamp" - this can be on the label and/or actually shaped in the glass itself, usually up higher on the flute-shaped bottle.

What about dry wine from the famed Mosel (including the Saar and Ruwer)? In general, the Mosel is identified with sweeter-style Rieslings, and rightly so - they combine sweetness with an agile acidity and tense minerality in a way just no other region does. The dry wines, with some important exceptions, seem to be less inspiring, especially from the well-known Middle Mosel vineyards. The growers who do make dry wines - usually in the Lower Mosel or in the Saar-Ruwer, where dry styles are more successful, and therefore more common - usually just label the wine "Trocken," or dry - such as in the example of Knebel's great Spatlese Trocken. This is a wine, in other words, whose grapes were picked at a Spatlese level of ripeness, but was fermented until it had 8 or fewer grams of RS per liter. We also carry a "Kabinett Feinherb" from Knebel - this wine was picked at a lower ripeness level (presumably) and fermented till it had, roughly, between 9 and 18 grams RS.

What about dry wine from the famed Mosel (including the Saar and Ruwer)? In general, the Mosel is identified with sweeter-style Rieslings, and rightly so - they combine sweetness with an agile acidity and tense minerality in a way just no other region does. The dry wines, with some important exceptions, seem to be less inspiring, especially from the well-known Middle Mosel vineyards. The growers who do make dry wines - usually in the Lower Mosel or in the Saar-Ruwer, where dry styles are more successful, and therefore more common - usually just label the wine "Trocken," or dry - such as in the example of Knebel's great Spatlese Trocken. This is a wine, in other words, whose grapes were picked at a Spatlese level of ripeness, but was fermented until it had 8 or fewer grams of RS per liter. We also carry a "Kabinett Feinherb" from Knebel - this wine was picked at a lower ripeness level (presumably) and fermented till it had, roughly, between 9 and 18 grams RS.

And there you go!